The Tree for the Righteous at the End-Time

(1 Enoch 24-26)

By Philip Esler and Angus Pryor

During the course of his angel-guided tour of the cosmos, when he has journeyed to the west (23:1), Enoch sees seven glorious mountains, three to the east (one set on the other), three to the south (one set on the other) and the seventh in the midst of them 24:1-12).70 It was higher than the others and was like the seat of a throne, with fragrant trees encircling it. Among those trees, Enoch comments, ‘was a tree such as I had never smelled … It had a fragrance sweeter smelling than all spices, and its leaves and its blossom and the tree never wither. Its fruit is beautiful, like dates of the palm trees’ (24:4). Enoch asks Michael, the angel then accompanying him, to explain this tree (24:5-25:2). He learns that the high mountain is like the throne of God, ‘the seat where the Great Holy One, the Lord of glory, will sit, when he descends to visit the earth in goodness’ (25:3). No human being is able to touch this tree ‘until the great judgment, in which there will be vengeance on all and a consummation forever’ (25:4). In the description of God’s end-time descent onto the earth for judgment in 1 Enoch 1:4-9, Mount Sinai is the mountain that serves as the staging-post for God and his angelic army after leaving heaven to judge humanity; perhaps the reader is meant to identify this high mountain with the tree in 1 Enoch 24-25 as Sinai.

Yet Enoch now learns something truly remarkable. After the judgment the tree will be transplanted to the holy place, meaning Jerusalem, next to the house of God (meaning the Temple). It will be given to the righteous and the pious and the chosen will use its fruit as food. They will rejoice and gladly enter the Temple with the fragrances of the tree in their bones and

they will live a long life on the earth, such as your fathers lived also in their days, and torments and plagues and suffering will not touch them (25:6).

Some commentators regard this tree as the ‘tree of life’ mentioned in Genesis 2-3.71 These chapters of Genesis actually mention two trees growing in the garden of Eden in the east that God planted: the tree of life in the midst of the garden and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil (2:8-9). God told Adam that he could freely eat the fruit of every tree in the garden, except of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, and if he did that, he would die on that day (2:16-17). After this God formed Eve from Adam (2:18-25) and Adam must have told her of this divine prohibition, since she repeated it to the serpent, saying that God forbade them eating from the fruit of the tree in the midst of the garden (3:1-3). The serpent understood her to mean the tree of the knowledge of good and evil (not the tree of life), even though it was the tree of life that was explicitly located in the midst of the garden (in both the Hebrew text and the Septuagint), since he told her that when they did eat its fruit they would know good and evil (3:4-5). So both Eve and then Adam ate of its fruit (3:6-7). God soon confronted them with the charge, ‘Have you eaten from the tree from which I commanded you not to eat?’ (Gen 3:11) and outlined the consequences of their doing so (3:17-19). Later, God was concerned that, having eaten of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, Adam might also eat from the tree of life and thereby gain immortality (3:22). So he drove him (and presumably Eve with him) out of the garden of Eden, while east of Eden he placed cherubim and a flaming sword ‘to guard the way to the tree of life’ (3:23-24).

Did the author (or authors) of 1 Enoch 24-25, therefore, intend their audience to identify the tree mentioned there with the tree of life in Genesis 2-3? Certainly, and critically, like the tree of life in Genesis, no human being is able to touch it, at least until the final judgment, and after that event the righteous will eat its fruit and gain life. Admittedly, the tree in 1 Enoch 24-25 is not called the ‘tree of life’ and the life it grants is not everlasting (as in Gen 3:24) but ‘long.’ Nor is it described as being in Eden but in a mountain in the west that could be Sinai. Charles answered the latter problem by suggesting that ‘the tree of life was moved from the earthly Eden to the Garden of Righteousness, and will thence be moved to Jerusalem’.72 While the idea of two translations is a useful one, this solution raises a further complication. The ‘paradise of righteousness’ features in a later section of the text, in 1 Enoch 31-32, when Enoch is journeying through another section of the cosmos, in the east (31:1), indeed, far in the east (32:2). Here he passes by the paradise of righteousness and sees more mountains and more trees, including one he called ‘the tree of wisdom’. Enoch comments that the holy ones eat of it and learn great wisdom (32:3). He describes it as follows:

That tree is in height like the fir, and its leaves, like (those of) the carob, and its fruit like clusters of the vine—very cheerful, and its fragrance penetrates far beyond the tree.

When Enoch expresses admiration for the beauty of the tree, the angel with him (Gabriel probably) replies:

This is the tree of wisdom from which your father of old and your mother of old, who were before you, ate and learned wisdom. And their eyes were opened, and they knew that they were naked, and they were driven from the garden (32:6).

In the Enochic picture, therefore, we have, on a mountain in the west, a tree that is recognisably like the tree of life, and another, in the east, which is expressly identified by Enoch with the tree of the knowledge of good and evil in Genesis 2-3. Veronika Bachmann, however, has recently mounted an innovative argument that the tree in 1 Enoch 24-25 is to be identified with Wisdom.73 Yet this view is difficult to reconcile with the two features of this tree that do align with the Genesis tree of life (that it is forbidden to human beings and will ultimately give life) and with the fact that it is the tree in 1 Enoch 32 that the text expressly links with wisdom. On the other hand, Charles erred in suggesting the tree in 1 Enoch 24-25 was located in ‘the paradise of righteousness’, for which we must wait until 1 Enoch 32. The tree like the tree of life is not growing there but on a mountain in the west.

Turning now to the painting, The Tree for the Righteous at the End-Time (1 Enoch 24-25), the artist has fixed upon the tree in 1 Enoch 24-25 for his subject, but at the particularly dramatic moment when God has descended from heaven to initiate the last judgment. In 1 Enoch this event is described at the start of the work (1:4-9), presumably to assure its audience that in spite of the horrors that will later be described as afflicting humanity in general, Israel and the cosmos, God will eventually prevail over evil, punishing the wicked and rewarding the righteous. The artist has imagined a scene where God’s descent upon the mountain brings him directly above the Tree for the Righteous. He has predicated the painting on the premise that the Tree for the Righteous was like no other tree known to humanity. The artist has grasped the idea of creating a painterly, metaphysical tree by using a post-conceptual process. The elements in the text, once translated into paint, create a new and dynamic image. William Blake’s Ancient of Days (1794) has served as a compositional device, while one senses the influence of Samuel Palmer’s painting Early Morning (1825) for its use of an isolated tree within landscape.

A major stroke of painterly originality is that within the painting, rather than God creating the Tree, God is the Tree, with knowledge his knowledge, righteousness his righteousness. His head is at the crown of the tree. He is depicted as God, but painted with facial characteristics that are used for positively regarded figures in Ethiopian painting. He is surrounded by a halo in the Ethiopian colours of orange, yellow and red. Immediately underneath his beard is an Ethiopian cross, partly to reflect his status and partly reflecting the wood of the tree. Above him, a quarter sun suggests the pathway to heaven for the righteous, post-judgment. In the sky, there are two symmetrical clouds underneath the head of the deity that represent the sustenance for the tree and its means of proliferation. Also in the sky, creatures framed by gold spheres congregate around the tree to denote its heavenly status. The two birds with spotted wings, which evoke some of the Ethiopian birds depicted in the Garima Gospels, act as the Watchers, guarding the deity.

As a compositional device, the viewer’s eye is led down directly into the mass of the main tree. Beneath the Godhead, the boughs of the tree are in symmetry. On these boughs grow a myriad of fruit like no other, ‘beautiful, like dates of the palm trees’ (24:4). Some fruits are created in two dimensions, by taking exotic fruits and printing them with paint on to the canvas. The colours chosen distinguish them as unearthly, imagined fruits. There are also three-dimensional fruits that sit on the surface like dates. The whole concept of these fruit is that anyone worthy enough to eat them will be deemed one of the righteous. There are birds nesting within the tree, including three-dimensional guinea fowl that are recognisably Ethiopian birds. These guinea fowl nest, partly for their own protection, but also as guardians of the tree. Insects, ladybirds and bees also gravitate to the tree, helping to pollinate it. The artist has chosen a composition that allows the viewer to see a myriad of images at once, with the essence of the tree as the main focal point. This was in part a device to suggest a sense of smell, with the artist leading the viewer to look at the strange fruits and to think that they could smell them within a visual narrative: ‘It had a fragrance sweeter smelling than all spices’ (24:4).

The painting compositionally is grounded by the earth. This is a flat earth, with nothing else growing in this scene other than the Tree for the Righteous that springs up like an eternal fountain. Mushrooms and insects gather around the bottom of the tree to represent a pilgrimage of mankind to the Tree after the last judgment.

The two deer heads and the antler represent the Nagar of 1 Enoch 90:38, discussed above, and thus link this painting to the larger structures of 1 Enoch and the Enochic tradition.

The muted colours are Ethiopian in character, with the gold depicting the celestial. The relationship between the two-dimensional and the three-dimensional creates a sense of space in the painting, bringing the Ethiopian flatness of style into a contemporary context. Overall this painting is an assault on the senses, with the viewer becoming a participant in the End-time congregation around the Tree following its transplantation to Jerusalem after the Judgment. The painting allows such participation to be realised in a way that transcends exposure to the text alone. The painting also escapes the narrative sequencing of the text by foregrounding central textual features in one experience and moment of visual and ideational comprehension. The painting thus honours the text by creating theological linkages simultaneously and sensorially. In sum, this painting is a celebration of the Tree for the Righteous.

On to the next painting?

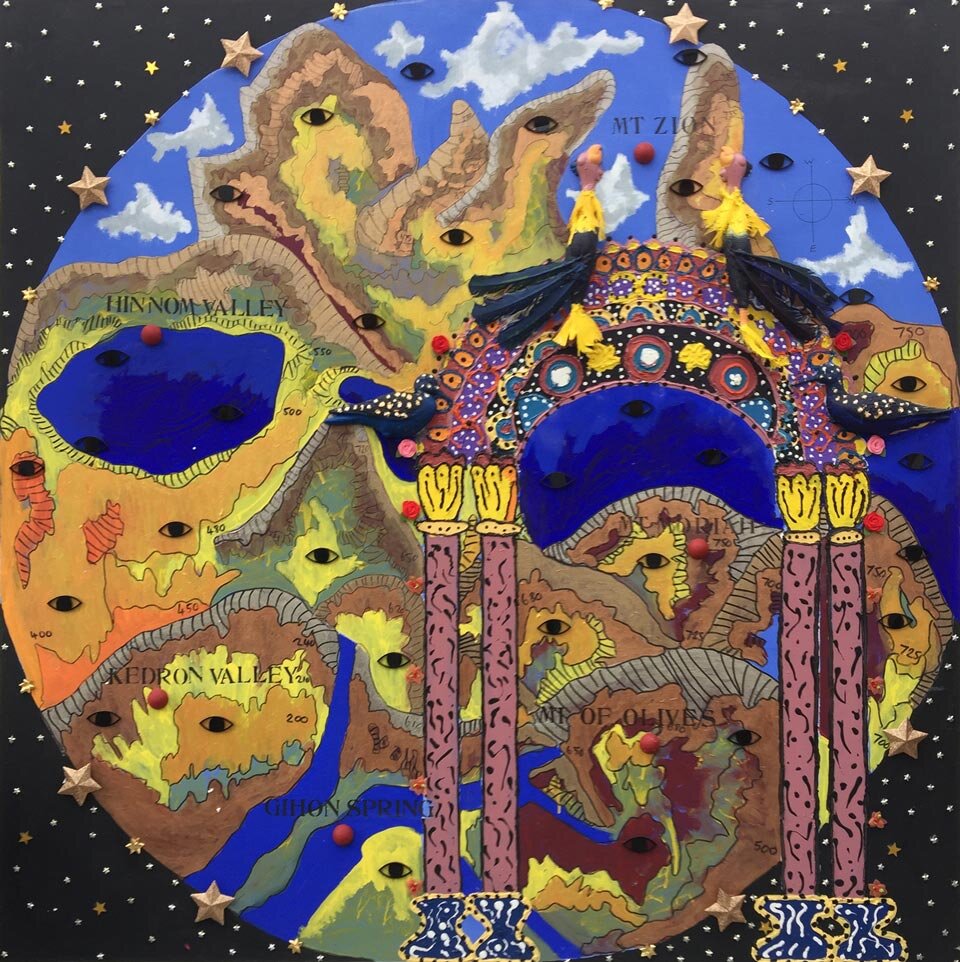

The Topography of Jerusalem

__

70 The discussion of this painting is gratefully reproduced by permission of the Biblical Theology Bulletin, Volume 50:3 (August 2020), 136-153, in an article entitled ‘Painting 1 Enoch: Biblical Interpretation, Theology, and Artistic Practice’, by Philip Esler and Angus Pryor.

71 R. H. Charles, ‘Book of Enoch’, in The Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha of the Old Testament in English. Volume II: Pseudepigrapha, by R. H. Charles (Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1913), 188-277, at 205; Nickelsburg, 1 Enoch, 314.

72 Charles, ‘1 Enoch’, 205.

73 Veronika Bachmann, ‘Rooted in Paradise? The Meaning of the “Tree of Life” in 1 Enoch 24-25 Reconsidered’, Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha (2009) 19: 83-107.