Introduction

by Philip Esler

1 Enoch has been described as the most important ancient Jewish writing not to have been included in the Old Testament. It was composed in the apocalyptic genre which, broadly speaking, refers to works containing a revelation (Greek: apokalypsis) in narrative form given by a heavenly figure to a human being concerning the nature of the cosmos and the secrets of God’s divine purpose for humanity and for creation and its renewal.13 It was written in Israel, in Aramaic, in stages from about 300 BCE to 100 CE by a group of scribes who formed around Enoch as their eponymous hero and revealer. Genesis 5.23-24 states that when Enoch was 365 years old God took him to heaven while he still lived. Accordingly, the Enochic scribes envisaged Enoch as a member of God’s heavenly court, among its angelic courtiers,14 and thus ideally placed to speak of the cosmos and God’s concern for it and humanity. Ancestors of these scribes had brought back from exile in Babylon in the sixth and fifth centuries BCE Babylonian astronomical knowledge and this featured prominently in the revelations they placed in Enoch’s mouth. They were also keenly interested in the problem of evil, both as it impacted on individuals and on the physical world, and looked forward to God’s final establishment of justice among all people and his renewal of creation.

Around 100 CE 1 Enoch was translated into Greek and its central verse (1 Enoch 1.9) is quoted with approval, and thus sacralised, in the New Testament in Jude 14-15. But within a few centuries it had almost entirely disappeared in the Christian world. Fortunately, in the fifth or sixth centuries CE the Greek text was brought to Ethiopia and translated into Ethiopic. 1 Enoch came to be regarded as part of the Old Testament in Ethiopian Orthodoxy and, uniquely in Christianity, played an important role in its theological and artistic traditions. The work was restored to the rest of world when the Scottish traveller James Bruce brought back copies from Ethiopia to Europe in 1773.15 The English translation of the Bodleian copy by Richard Laurence in 1821 (the first in a European language) exposed the text to widespread scholarly and popular interest that has continued ever since. The world has Ethiopia to thank for the preservation of 1 Enoch.

Further developments have added to the allure of the work. Thus, the subsequent discovery of a Greek version of most of 1 Enoch 1-36 in a monk’s grave in Akhmin in Egypt in 1886/87 soon stimulated more research, especially on the Ethiopic text.16 Just as significantly, the Aramaic fragments of four of 1 Enoch’s five main constituent parts, the original form of the text, were found in Cave 4 at Qumran.17 This discovery led to further research into the Ethiopic text of 1 Enoch.18 Then came major commentaries.19 There has, in short, been a multitude of books, articles and essays published on 1 Enoch.20

Yet, in spite of this efflorescence of scholarship on the text, something was missing, at least in the West, namely its role in theology. In Ethiopia, on the other hand, there has long been interest in the theological use of 1 Enoch, especially as a text that brings together many aspects of the history of redemption. In particular, the indigenous Ethiopian commentary, the Andemta (written in Amharic and Ge’ez, floruit 16th to 18th centuries CE), interprets 1 Enoch as a Christian text and as one that is in harmony with the rest of the Bible. The Andemta is both an ancient tradition and very much a living and contemporary one. 1 Enoch has also influenced Ethiopian culture in other ways. The image of paradise in 1 Enoch 25, for example, has provided the rationale for building churches (which symbolise Paradise) in precisely such an arboreal setting. As a result, some of the most extensive surviving forests in northern Ethiopia exist on church property. 21 Archangels mentioned in 1 Enoch frequently appear in Ethiopian churches and on Ethiopian prayer scrolls.

In Western countries, however, until very recently virtually all the research carried out on 1 Enoch had been historical in nature; that is, it concerned what the text meant in the ancient world and how it casts light on phenomena and other texts in that setting. Virtually no serious study had been made as to what theology can be generated from the text itself; that is, into what insights it can yield into the human situation and our understanding of God. This was a surprising and regrettable scholarly lacuna. The capacity of the text to generate fresh insights about the problem of evil, the ecological crisis and questions of social justice, to name just a few areas, is self-evident on even a passing reading. The neglect of 1 Enoch as theology also sat oddly with the fact that 1 Enoch is scripture in Ethiopian orthodoxy and that the Epistle of Jude in the New Testament summarises part of its primary narrative, the fate of the Watchers (rebellious angels), in v. 6 and, as already noted, quotes its summative verse, 1 Enoch 1:9, in vv. 14-15.

At the meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature in Baltimore in November 2013, Philip Esler and Loren Stuckenbruck, Professor of New Testament in the University of Munich, discovered that they both shared an enthusiasm for the potential of 1 Enoch to be an exciting source of contemporary theological thought. Joining forces with Grant Macaskill, who shortly thereafter became Kirby Laing Chair of New Testament Exegesis in the University of Aberdeen, they successfully applied to the British Academy in 2014 for a grant that funded two meetings of Ethiopian and Western theologians in 2015—one in Addis Ababa, hosted by Dr Daniel Assefa, then Director of the Capuchin Franciscan Research and Conference Centre, in February, and one in Cheltenham in October. Before the Addis Ababa meeting they were joined by Angus Pryor, Head of the School of Art and Design at the University of Gloucestershire. He had become greatly interested in 1 Enoch having attended Esler’s inaugural lecture in 2014 on the presentation of heaven in 1 Enoch 1-36 and had begun thinking about the text in artistic terms. Pryor and Esler both experienced Ethiopian art and ecclesial architecture (where much of that art is located) while attending the Addis Ababa meeting in 2015 and during another and lengthier visit they later paid to northern Ethiopia in 2017. During these visits they continually encountered connections with features of the text of 1 Enoch.

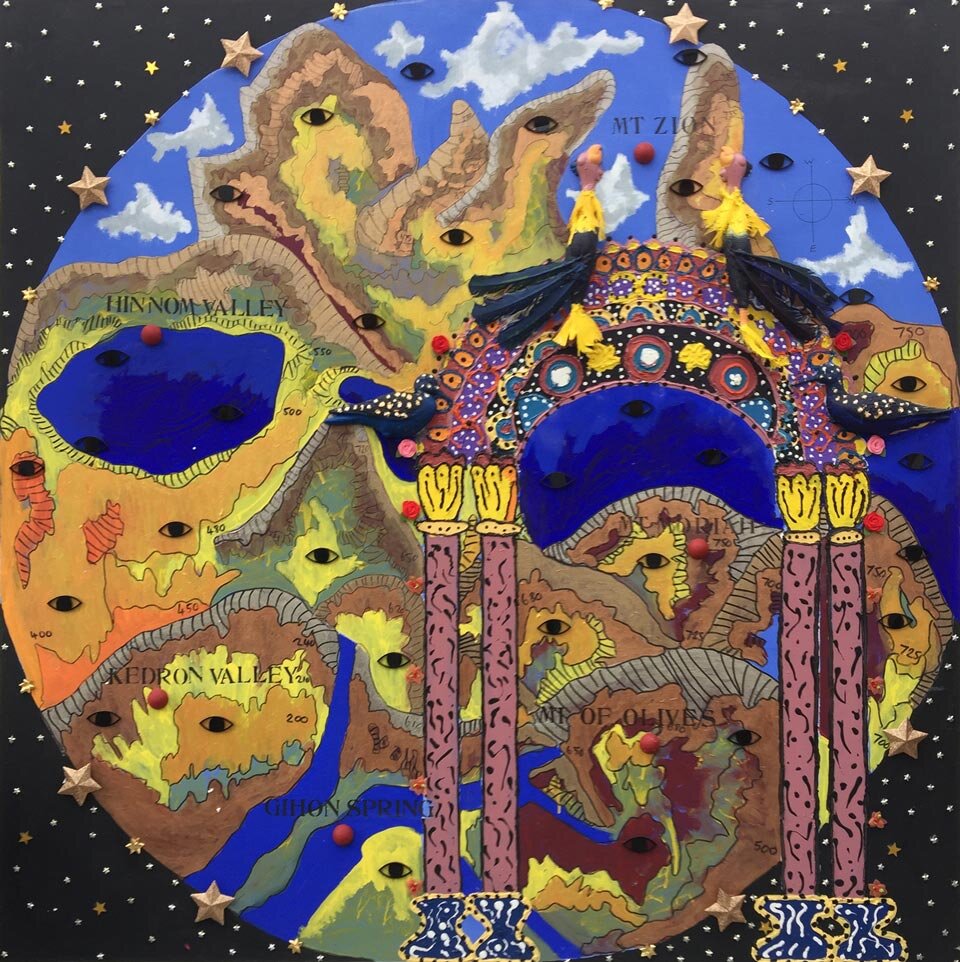

A selection of papers delivered at the two meetings was duly published in 2017 as The Blessing of Enoch: 1 Enoch and Contemporary Theology, thus initiating this new area of theological research.22 One of the essays in the book was by Pryor and entitled ‘Enoch: An Artist’s Response’. 23 It set out a programme for painting a series of canvases on 1 Enoch that would permit him to explore the theology of the text from the perspective of practice-based research. In the essay Pryor made clear his great debt to Ethiopian traditions of painting and iconography.

In due course, and in homage to the numerous Ethiopian Orthodox churches he and Esler had visited in Ethiopia—including in Aksum, Lalibela and Gondar—Pryor decided to add to the twelve paintings a large-scale model of an Ethiopian church, illuminated with traditional Ethiopian imagery and Enochic themes, a virtual Church of St Enoch. Pryor has completed the bulk of the work on the paintings and the Church since 2017, with advice from Esler on the scenes from the text to be included and aspects of the form and decoration of the church.

The collaboration between Pryor and Esler on this exhibition also builds upon their earlier joint involvement with still small voice: British Biblical Art in a Secular Age (1850—2014), an exhibition of contemporary British biblical art from the Ahmanson Collection at the Wilson Gallery in Cheltenham in January-February 2015. Pryor curated this exhibition and created for it a three-dimensional transcription of Stanley Spencer’s painting Angels of the Apocalypse while Esler worked on the accompanying academic programme. The still small voice exhibition and the exhibition Enoch: God’s Messenger form parts of their larger project on painting the Bible, which embraces both practice-based research and involvement of partner organisations and the wider public in the various forms of illumination and transformation that can be stimulated by exposure to the process and results of visualising biblical texts.

Philip Esler

Portland Professor in New Testament Studies,

University of Gloucestershire

June 2020

View the collection of paintings

God and the End-Time Punishment

__

13 The translation of 1 Enoch in The Book of Enoch, translated by R. H. Charles, with an introduction by W. O. Oesterley (London: SCM, 1917), is available online: https://www.sacred-texts.com/bib/boe/index.htm

14 See Philip F. Esler, God’s Court and Courtiers in the Book of the Watchers: Re-interpreting Heaven in 1 Enoch 1-36 (Eugene, OR; Cascade, 2017).

15 On Bruce, see Miles Bredin, The Pale Abyssinian: A Life of James Bruce, African Explorer and Adventurer (London: Flamingo, 2000).

16 See Robert Henry Charles, The Book of Enoch (Oxford: Clarendon, 1893) and Johann Flemming, Das Buch Henoch: Aethiopischer Text (Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs, 1902).

17 J. T. Milik, The Books of Enoch: Aramaic Fragments of Qumran Cave 4. With the collaboration of Matthew Black (Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1976).

18 Michael A. Knibb, in consultation with Edward Ullendorff, The Ethiopic Book of Enoch: A New Edition in the Light of the Aramaic Dead Sea Fragments. Two volumes (Oxford: Clarendon, 1978).

19 George W. E. Nickelsburg, 1 Enoch. A Critical Edition on the Book of 1 Enoch, Chapters 1-36; 81-108. Hermeneia Commentary (Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg Fortress, 2001); George W. E. Nickelsburg and James C. VanderKam, 1 Enoch 2: A Commentary on the Book of Enoch Chapters 37-82. Hermeneia (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2012); and Loren T. Stuckenbruck, 1 Enoch 91–108 (Berlin: de Gruyter, 2007).

20 See the comprehensive list in James H. Charlesworth and Ephraim Isaac, O Livro de Enoque Etíope ou 1 Enoque, trans. Orlando Iannuzzi Filho (Sao Paulo: Entre os Tempos, 2015), 249-526.

21 This was the subject of a BBC radio programme on 30th August 2019: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/w3cszbx0

22 Philip F. Esler (ed.), The Blessing of Enoch: 1 Enoch and Contemporary Theology (Eugene, OR: Cascade, 2017).

23 Ibid., 191-195.